(This is the second in a series of posts about recent books about history and business in Nebraska.)

In the Spring of 1867, one Sidney Buffett left Long Island, New York, where his family had lived and worked since the 1600s, and took a train West to Omaha. There his maternal grandfather, George Homan, owner of a livery stable and operator of the local stage line, gave him work and introduced him to the local business community. Two years later, in 1869, Sidney Buffett opened a grocery store on south 14th Street in Omaha.

The Buffett grocery business would last through three generations and 100 years. It supported and often employed Sidney's progeny, a large, hard working, prosperous, civic-minded, politically involved Omaha family. The Buffetts, always proud of their grocery's pioneer status among Omaha businesses, built their understanding of what mattered in life from their experiences as tradesmen. If family came at the top of that list, success in business was right beside it. In trade, they could not affort to be profligate, or greedy, or to seem so. They were careful with their money. They valued hard work. They were reminded every day of the value of their connections with customers, employees and other businesses. Day by day, in small things as in large ones, they cultivated good relationships with others. They were intensely practical, and when they saw troubles ahead, they saved enough money to sustain their business in hard times. By this means, they grew their business through two terrible depressions, one in the 1890s and another in the 1930s. Buffett's lasted until 1969, and closed then only as regional chains and supplier combinations threatened their profitability.

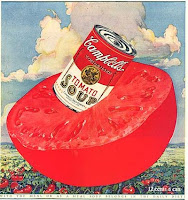

Bill Buffett's book, Foods you will enjoy: The story of Buffett's Store. (Concord: Capital Offset Company, 2008) is the story of the Buffett's Omaha grocery business. The author is Sidney Buffett's great grandson. The book draws on the family's letters and photographs, on local museum collections and old newspapers, on reminiscences by several generations of the Buffetts themselves and by their former employees and customers, and on the author's collection of contemporary advertising materials. All in all, this is very rich source material. For many years, Buffett's store was a community institution in a way that businesses once were but no longer seem to be.

The history of the store is told in three dimensions. The first dimension is a narrative, following family memories, letters and local and business history. A second dimension is the inclusion of many telling excerpts of the source material itself, including letters, contemporary newspaper articles, business documents, and letters and later reminiscences by former employees and customers as well as by the Buffetts themselves. A third dimension is a graphic history, integrating photographs, period media reports, and period advertising materials. Some of the advertising is seen displayed in the store in period photographs, some is now reproduced in color to give the book a real graphic punch. In each of these three dimensions, the book is strikingly well conceived. Each of the three perspectives could almost carry the story by itself.

Librarians and scholars are sometimes unjustly skeptical of self-published works. Although this book would be considered self-published, it was professionally designed by Book Designer Rick Rawlins. Not surprisingly, it won an AIGA 2009 "Best of New England" Design award for its designer. Throughout, the book is a reminder that technology now makes it possible to create very high quality books whose expected publication runs are so small that previously, they could never have been published at all.

Some of the more memorable things about the book, for this reader, include: The character of Ernest Buffett, as it shines through in the business and family advice he wrote to his sons. The very different way people used to shop, with a clerk gathering individual items from a written list while the customer browsed.

Credit too was handled differently. Like one of the Buffetts' customers, in the midst of the Depression of the 1930s, my own grandmother bought the family house outright with cash borrowed at a grocery store, and paid it all back with interest in a year, along with her monthly grocery tab.

Not every Buffett went into the grocery trade. One of Sidney's grandsons, Howard Buffett, went off to college wanting to be a journalist. Marriage, and evidently, an effective admonition from his grocer father, led Howard to the more practical, better paying business of selling insurance. In time, Howard moved on to be a stockbroker, then Republican congressman from Omaha.

Howard's son, Warren Buffett, the investor, would become the most famous Buffett of all. Warren has said that his start in business came at Buffett's Store. For some months in 1943, Warren Buffett lived with and worked for his grandfather. In his own short contribution to this book Warren Buffett recalls that his job at the time was to take dictation from Ernest, who was writing a book whose title was to be "How to Run a Grocery Store and a Few Things I Have Learned About Fishing." Grandpa Buffett, Warren recalls, "considered these to be the only two subjects really worthy of commentary."

The author is an insightful historian. He remarks at the beginning of the book that nowdays he buys his toothpaste at a chain store with more than 5,700 outlets in the United States, and he recalls a time when he bought that toothpaste in a local one-of-a-kind drug store. His book seems to remind us of aspects of character and community that we still need, but find hard to sustain as arrangements of work and family life that built them fall by the wayside.

This is Bill Buffett's second book. His first, also recently added to our collection, is a memoir of his mother, Katherine Armina Norris Buffett (June 13, 1906-August 17, 2004). Dear Katherine (Self published by Bill Buffett, 2005) is a family scrapbook. It combines Katherine's own memoir about her early life with family photographs, excerpts from letters she wrote and that others wrote to her, some of her recipes, poetry she cut from the newspaper, and so on. Scattered throughout the book are envelopes with onionskin sheets on which are printed the texts of various letters from people recalling Katherine or thanking her for some of the many things she did for others.

The book design is interesting. It evokes a family scrapbook with a precious archive of letters pressed between the pages, but the packets of onionskin letters are fragile, and in consequence the book will not stand up to use by many hands.

Like the later book, Dear Katherine succeeds in what it sets out to do. Katherine's warmth, generosity and sense of humor shine through. It is also an interesting portrait of a midwestern woman of her generation.

Almost all of the materials reflect Katherine's careful cultivation of the informal connections of kinship, friendship and community. These materials testify to the great value her generation placed on such connections, as well as to the way the women of that generation shaped their own lives in a time when the making of a healthy social world was largely women's work. The Foreword reveals the intensity of Katherine's attention to connection. Bill Buffett writes that in the last weeks of her life, when they had spoken openly about her dying, "She looked away, then at me and asked'How will we stay connected.' I assured her we would. This book is part of that effort."

These books are quite interesting and are valuable entirely on their own. They have much to tell us about life and business and community over the past century. But it is probably inevitable that some readers will be mostly interested in the Warren Buffett connection. Alice Schroeder's thorough and much admired 2008 biography, The Snowball. Warren Buffett and the Business of Life, covers some of the same territory, and shows that Warren Buffett is a very complex character.

Taken together, these books reveal many common threads and shared understandings between Warren and the larger Buffett family. The most striking, for this reader, grows from the family's consciousness of the importance of connection, and their realism, judiciousness and generosity in building networks of business associates and friends. Whatever its other resources, genius needs a firm grip on reality to succeed, and in schooling their generations in the care of connections with their community, the Buffett family created a kind of 'Buffett brand' of realism that appears to survive in Warren Buffett's way of doing business.

Stephen Cloyd